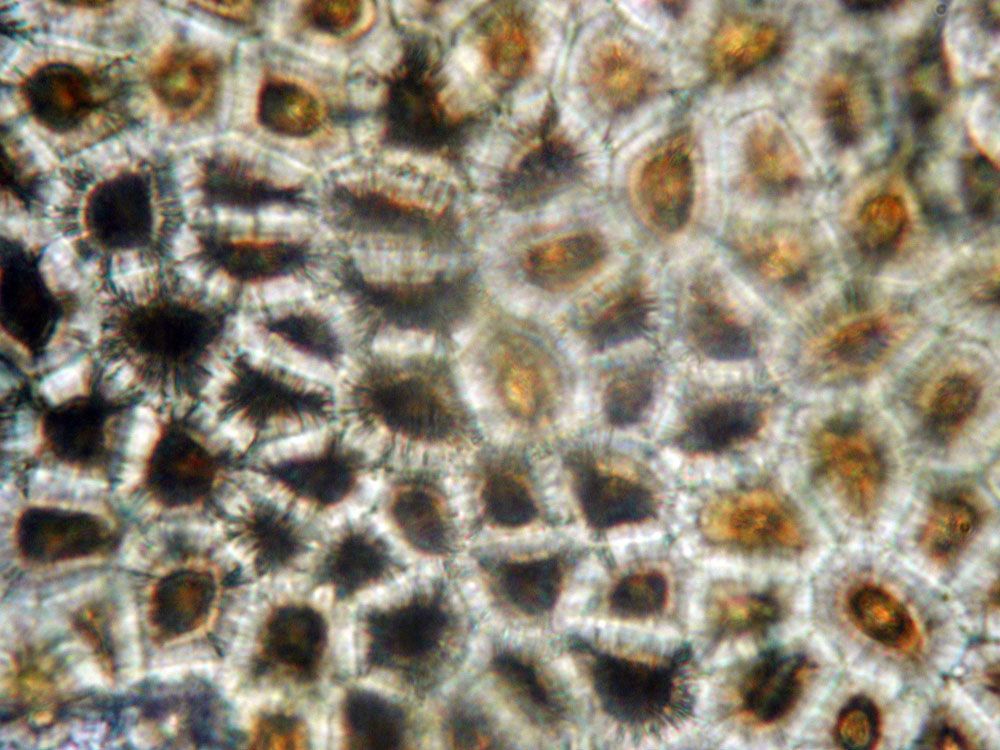

Asari Radix et Rhizoma, Xi xin

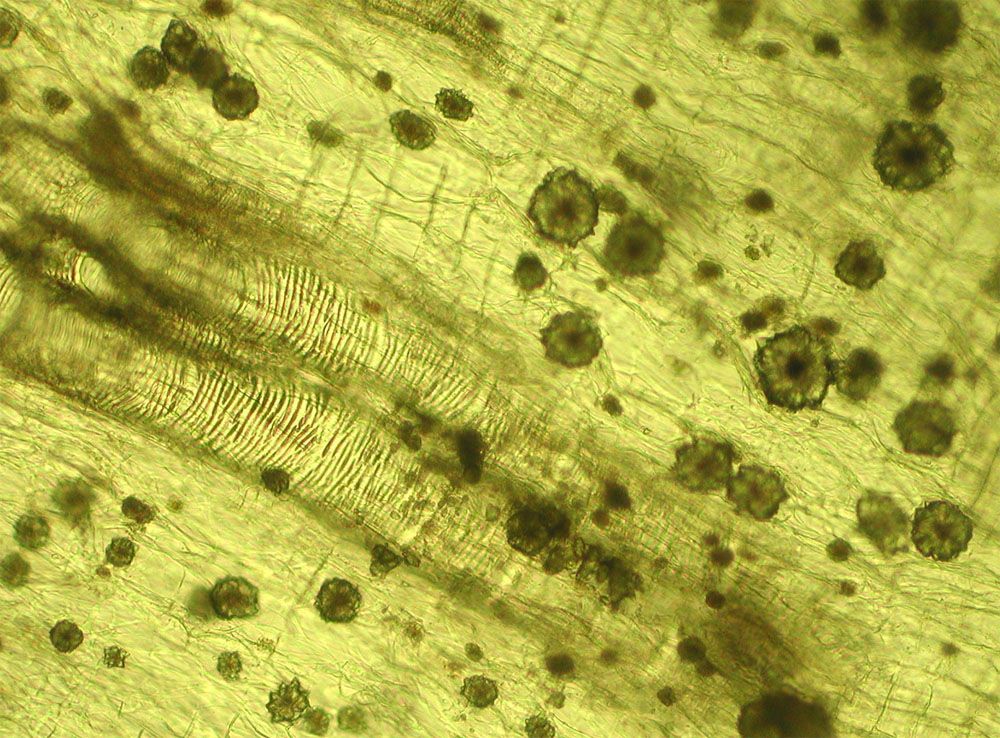

Asari Herba, Xi xin

The Safety of Asarum – An Evaluation

Translated by Friederike Wunschik from an article in German published in Deutsche Zeitschrift für Akupunktur 54(2), 2011:47-50

Axel Wiebrecht

After the discovery in the 1990s that aristolochic acid (AA)-I and -II were associated with severe nephropathy and urothelial carcinoma, aristolochic acid was also found in Asarum species. However the amounts of both AA-I and AA-II found in officinal Asarum species are mostly very small and occasionally below the limit of detection (In comparison, non-officinal Asarum crispulatum contains high amounts of aristolochic acid). Because of the aristolochic acid content, both Switzerland and Germany banned the medicinal use of Asarum in 2010. The risk tolerance chosen is extremely low when compared to that of conventional drugs or everyday hazards. A total ban of Asarum seems disproportionate.

Abstract

Xi xin – Asarum Radix et Rhizoma – is a classical herb in Chinese medicine. It is of vital importance in various prescriptions and difficult to replace. After the discovery in the 1990s that aristolochic acid (AA)-I and -II were associated with severe nephropathy and urothelial carcinoma, aristolochic acid was also found in Asarum ssp. However the amounts of AA-I and AA-II cited are mostly very small and occasionally below the limit of detection. In comparison, non-officinal Asarum crispulatumcontains high amounts of aristolochic acid. Because of the aristolochic acid content, both Switzerland and Germany banned the medicinal use of Asarum in 2010. The Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM), in banning the herb, argues that the only acceptable risk is a 50 percent life-time chance of developing a tumour in one in 1,000,000 persons after two years of drug-administration. This risk tolerance is extremely low when compared to that of conventional drugs or everyday hazards. A more realistic risk calculation might take into account the risk of death to the general population caused by the nuclear radiation that Germans are allowed to be exposed to each year by nuclear facilities. In such a calculation, the health risk posed by xi xin could, by prescribing a maximum length of administration and enforcing strict quality control measures on xi xin medicines, be reduced to a very tolerable level. A total ban of Asarum seems disproportionate.

Key words: Chinese herbal medicine, Asarum, Xi xin, aristolochic acid, nephropathy, tumor risk, adverse drug event

Introduction

Xi xin – Asarum Radix et Rhizoma – is a classic herb in Chinese medicine. It is mentioned in the first-known Materia Medica, the shen nong ben cao jing from the late Han dynasty. The Chinese medicine pharmacopoeia describes xi xin as acrid and warm, opening the exterior, dispelling cold, expelling Wind, Cold, Dampness and Phlegm, and relieving pain. It is predominantly used in the treatment of colds, cough with thin sputum, and also for head- and toothaches, as well as joint pain. It is an essential herb needed to treat a variety of diagnoses and is difficult to substitute.

Administration of this herb has traditionally been cautious; the official daily dosage of the raw herb lies between 1 and 3 grams [1]. Overdose may lead to unwanted side-effects or even death [2, 3]. Toxic reactions are due to safrole contained in the herb [3]. Safrole is considered to be a weak hepatocarcinogen and genotoxic. The safrole content is reduced through the process of decoction and by this means achieves acceptable levels [4].

A completely different set of problems arose during the 1990s, when aristolochic acids in Aristolochia herbs were found to be associated with many cases of terminal nephropathy in patients treated at a Belgian weight-loss clinic. After this incident, other cases were discovered worldwide [5]; many of those developed urothelial carcinomas [6]. Aristolochic acids were already known to be potent carcinogens and in Germany, herbs containing aristolochic acids were banned in 1981 [5]. While various countries were implementing safety measures and bans, Asarum plants were found to contain aristolochic acid. However, the levels of aristolochic acid in these plants, if it was detectable at all, were definitely lower than the levels measured in Aristolochia herbs.

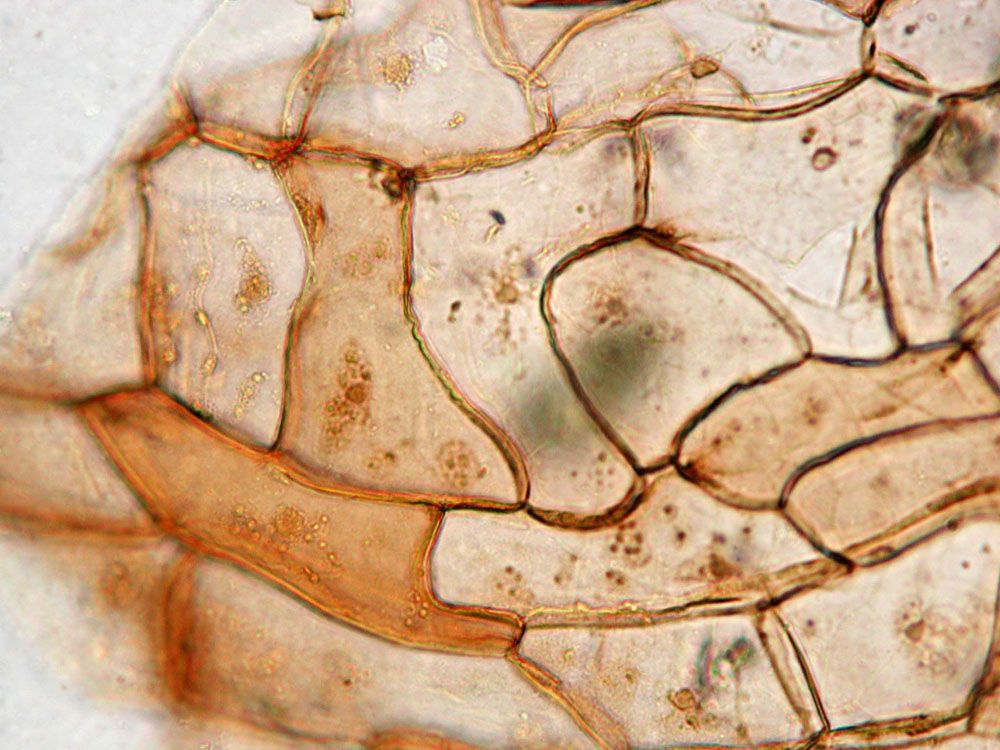

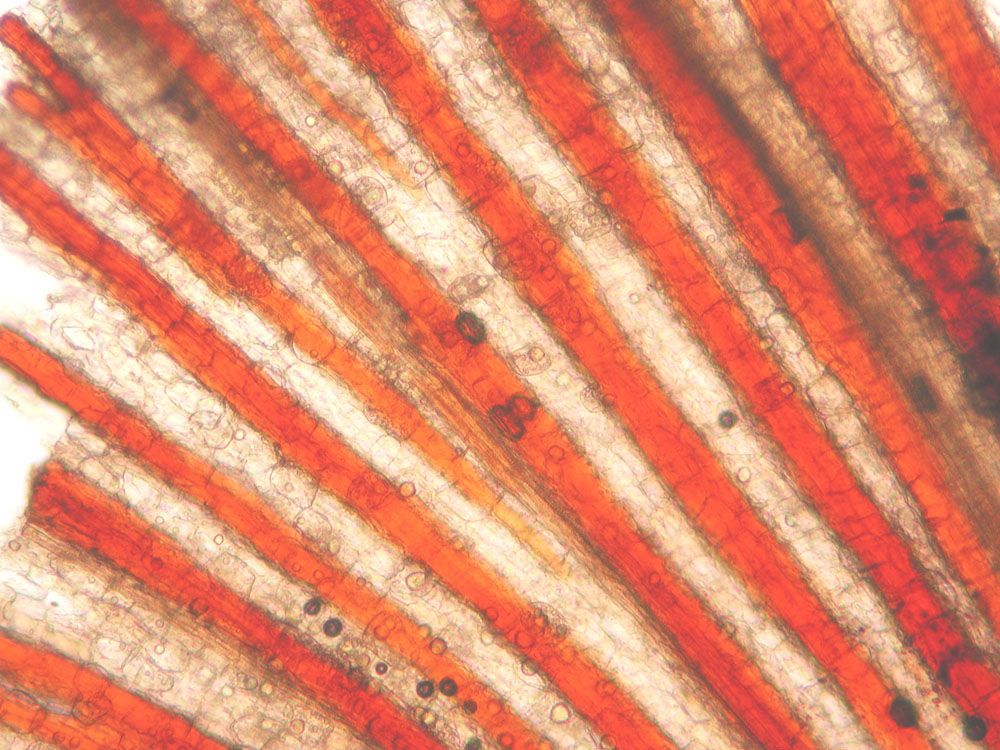

To reduce risk, the officially used part of the plant, that at first had been modified to herba – the aerial parts – due to availability issues, was changed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia to radix et rhizoma in 2005, because these parts contain less aristolochic acid. In 2004 Hongkong had already banned the sale of herba or planta tota ofAsarum, allowing only the use of radix [7].

Aristolichic acid in Asarum

Table 1 shows the levels of aristolochic acid documented in the Asarum species used in Chinese medicine [8-12]. Almost all the levels of aristolochic acid-I (AA-I) for those parts of officinal xi xin ssps. allowed for use in drugs (radix et rhizoma or just radix) are below 1 µg/g (marked in green); only one value of 2.16 µg/g is higher. The levels of aristolochic acid-II (AA-II) are generally lower and were only taken into consideration in some of the studies.

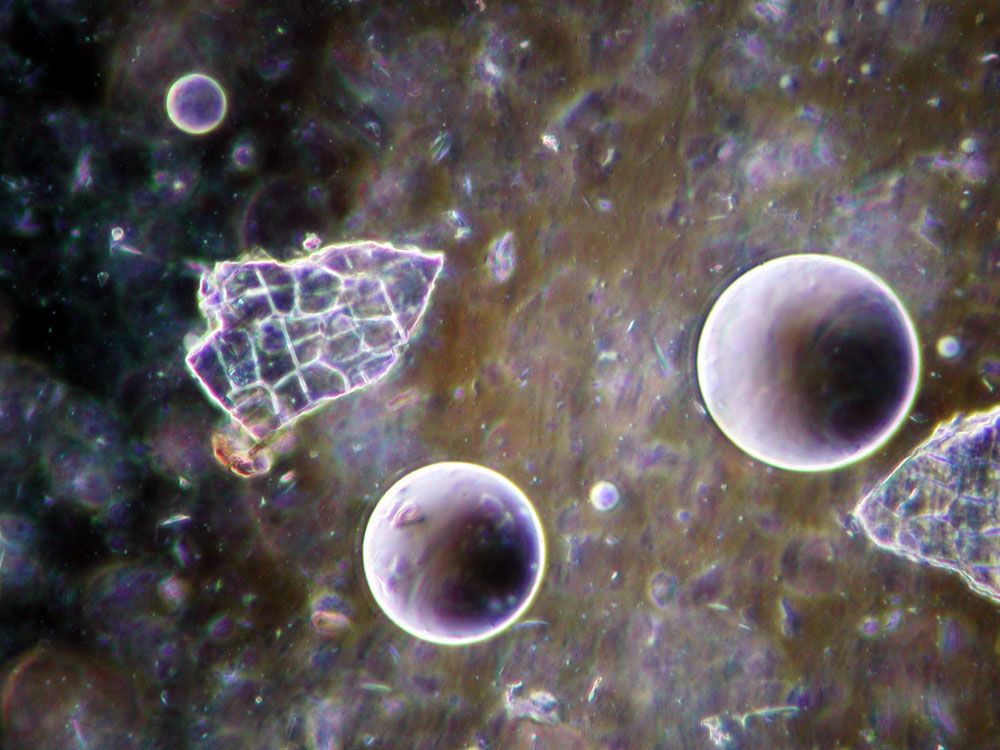

Zhao et al [12] compared the levels of AA-I in several samples of watery extract with those of methanolic extract. In a methanolic extraction the extract retains large amounts of the aristolochic acid of the plant, while water extracts closely resemble a decoction, depending on the extraction conditions. In this case the herb was soaked in water for 20 minutes and then boiled for 40 minutes. As shown in Table 1, water extraction reduces the level of aristolochic acid; when using radix it is reduced by a factor of 4.7 to 18.6. Granules are made from watery extracts and therefore equivalent reduced levels of aristolochic acid can be inferred. Pulverised raw xi xin should not be ingested, as it contains the full amount of aristolochic acid.

Other parts of the plant, specifically the aerial parts (herba) or the entire plant (planta tota), contain much higher levels of aristolochic acid. The highest published value is a troubling 142 µg/g. More dramatic values are found in non-officinal species, namely Asarum crispulatum, found in Sichuan and used as a local variant for xi xin, which contains a whopping 3,376.9 µg/g [9]. This value corresponds to a medium value found in the Aristolochia-herbs [8]. This shows how crucial the use of officinal drugs with valid confirmation of identity is.

Banned by the German BfArM

On July 22nd 2010 the use of all plants belonging to the Asarum species in drugs was banned in Germany by decree of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) [13]. The cause of this was the detection of AA-I in homeopathic mother tinctures of Asarum europaeum with levels of 5.1 and 2.7 µg/g. The decree also mentions studies that found higher levels of aristolochic acid, among them the above-mentioned values for Asarum crispulatum.

In its risk assessment the BfArM assumes a tolerable cancer lifetime risk of 1:1,000,000. Accordingly, with a linear dose-reaction-model for two years of administration, a virtually safe dose of 0.36 ng aristolochic acid per diem can be calculated. For homoeopathic remedies the above-mentioned highest documented level of aristolochic acid of 3,377 µg/g in Asarum ssp. is used as a base-value. Therefore a tolerable dose is not achieved until D9, and only at D11 is the dose considered non-hazardous. Assuming the lowest published level of aristolochic acid in a decoction of 0.04 µg/g made by officinal asarum medicines, then the “virtually safe dose” is just exceeded at 1g xi xin. But: are these assumptions realistic?

Unrealistic safety guidelines

To recap: the BfArM considers that the only acceptable risk for ingestion of aristolochic acid through herbal medicines is a 50 percent life-time chance of developing a tumor in one in one million cases. This safety guideline is however far more restrictive than the risks tolerated in conventional drugs.

According to the study carried out by the WHI, hormone replacement therapy was associated with 700 cases of coronary heart disease, 800 strokes, 1,800 cases of venous thrombosis, and 800 cases of invasive breast cancer in one million healthy women per year (!). The 500 hip fractures and 600 colorectal cancers less in those women are not on the scale of the negative results of that study [14]. Hormone replacement therapy is still approved; a discussion of whether this is justified or not is beyond the scope of this article. According to two three-year studies, the anti-diabetic drug Pioglitazone - which is controversial because of the increased risk of heart failure and fractures associated with it - increased the incidence of bladder cancer by 0.3% (absolute value) compared to those receiving placebo or glibenclamide. This is an increase in carcinomas of 3,000 in one million cases in this three-year period [15].

The difference in tolerated risk becomes painfully apparent, when considering every-day risks. Tobacco smoking at the time of first data collection, for instance, if one extrapolates the results of a twenty-year British study, was the cause of death in 99,485 out of 1,000,000 adults (extrapolation according to [16]). Nevertheless, tobacco products are widely available to all adults.

Of course, risk assessment should always take into account the benefits. However, the government drug authorities seem to employ an all-or-nothing rule: if the efficacy of a drug– however small it may be – is proven with an Ia or even an Ib evidence level then the occasional high risk is accepted; while a nearly-zero-risk-tolerance is in place concerning drugs with only experience-based efficacy. This methodology is inacceptable and half-baked. As the tobacco example shows – other examples would include alcohol, air pollution, and similar factors – this purism is not applied to other areas, although this does not at all mean that the lax attitude to these health-risks should be endorsed. One gets the distinct impression that conventional and complementary medicine are being measured with different yardsticks, which is probably due to the prevailing medical paradigm.

There are other ways of minimizing risk

A more realistic but nevertheless highly safe risk reduction could, for example, entail the following: Taking the BfArM’s way of calculation (which shall not be discussed here) and assuming a 50% life-time likelihood of tumour not in 1 in 1,000,000, but in 1 in 10,000 patients, this measure can be met by not exceeding a daily dosage of 3g raw herb and by limiting the period of administration to a maximum 6 weeks, if you apply a decoction made in standardised manner using herbs with a content of less than 0.1 µg/g of aristolochic acid (AA-I and AA-II combined). Staying within this limit of maximum aristolochic acid content would be possible if those species with low levels of aristolochic acid were to be used. In granules the content could be higher with reduced maximum dosage, analogous to the drug-extract rate.

The 50% tumour chance occurring in 1 in 10,000 cases – during a lifetime – corresponds to the risk of death by cancer that is expected every year from the maximum permissible radiation dose of 1mSV to which the nuclear facilities can expose the normal German population [17] (calculated with the assumption of a linear dosage-effect rate and using the data provided by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), which might be grossly underestimating the risk [18]).

Conclusion:

The cancer risk can be reduced to a minimal and acceptable value by guaranteeing the quality of xi xin herbs and herbal extracts, and by reducing the allowed length of administration. This entails verification of identity and testing for aristolochic acid with adequate methodology, as there are 30 different Asarum species and 4 sub-species in China and as adulterations are common [3]. Banning all use of Asarum is disproportionate and a significant loss of treatment options in Chinese herbal medicine.

Axel Wiebrecht, M.D.

General medicine, naturopathy, Chinese Medicine

Bundesallee 141

D-12161 Berlin

Tel. +49 (0)30 8591067

Literature:

- Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. Vol. I. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2005

- Drew AK, Whyte IM, Bensoussan A, et al. Chinese herbal medicine database: monograph on Herba Asari, "Xi Xin". Clin Toxicol 2002;40:169-172

- Bensky D, Clavey S and Stöger E. Chinese Herbal Medicine. Materia Medica. 3th ed. Seattle: Eastland Press, 2004

- Chen C, Spriano D, Lehmann T, et al. Reduction of safrole and methyleugenol in Asari radix et rhizoma by decoction. Forsch Komplementmed 2009;16:162-6

- Wiebrecht A. Über die Aristolochia-Nephropathie. Dt Zschr Akupunktur 2000;43:187-197

- Nortier JL, Martinez M-CM, Schmeiser HH, et al. Urothelial carcinoma associated with the use of a Chinese herb (Aristolochia fangchi). New Engl J Med 2000;342:1686-92

- Government of Hong Kong, Department of Health. Management of aristolochic acid (AA) containing herbs and products, 11 June 2004,http://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/news/AA_CMTraders_e.pdf

- Hashimoto K, Higuchi M, Makino B, et al. Quantitative analysis of aristolochic acids, toxic compounds, contained in some medical plants. J Ethnopharmacol 1999;64:185-9

- Jong TT, Lee MR, Hsiao SS, et al. Analysis of aristolochic acid in nine sources of Xixin, a traditional Chinese medicine, by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/tandem mass pectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2003;33:831-7

- Schaneberg BT, Khan IA. Analysis of products suspected of containing Aristolochia or Asarum species. J Ethnopharmacol 2004;94:245-9

- Jiang X, Wang ZM, You LS, et al. [Determination of aristolochic acid A in Radix Aristolochiae and Herba Asari by RP-HPLC] (Chinese). Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2004;29:408-10

- Zhao ZZ, Liang ZT, Jiang ZH, et al. Comparative study on the aristolochic acid I content of Herba Asari for safe use. Phytomedicine 2008;15:741-8

- BfArM. Aristolochiaceaehaltige Arzneimittel, die unter Verwendung von Pflanzen der Gattung Asarum hergestellt werden: Das BfArM ordnet den Widerruf der Zulassung an. Bescheid vom 22.07.2010: http://www.bfarm.de/cae/servlet/contentblob/1207042/publicationFile/9260..., date accessed 2010 Sep 1, 2010

- N.N. Hormone nach den Wechseljahren: der Skandal setzt sich fort. Arzneitelegramm 2002;33:81-3

- N. N. Blasenkrebs unter Pioglitazon (Actos u.a.). Arzneitelegramm 2010;41:108

- Kvaavik E, Batty GD, Ursin G, et al. Influence of individual and combined health behaviors on total and cause-specific mortality in men and women: the United Kingdom health and lifestyle survey. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:711-8

- Bundesministerium der Justiz. Verordnung über den Schutz vor Schäden durch ionisierende Strahlen, 2008

- Schmitz-Feuerhake I. Übersicht zu den Langzeitfolgen von chronischer Niedrigdosisbestrahlung. Strahlentelex 2006;20(460-461):1-5

| Species | Part | Extraction | Orign | AAI [μg/g] |

AAII [μg/g] |

Study |

|

Asarum sieboldii |

radix(?) |

ME |

Japan |

< 1 |

< 1 |

Hashimoto 1999 |

|

Asarum sieboldii |

radix(?) |

ME |

Japan |

< 1 |

< 1 |

|

| Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

radix(?) |

ME |

China, Liaoning |

< 1 |

< 1 |

|

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

radix(?) |

ME |

China, Jilin |

< 1 |

< 1 |

|

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

radix(?) |

ME |

North Korea |

< 1 |

< 1 |

|

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

radix(?) |

ME |

Liaoning |

< 1 |

< 1 |

|

|

Asarum sieboldii var. seoulense |

radix(?) |

ME |

Korea |

< 1 |

< 1 |

|

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

herba(?) |

MEc |

China |

42.2 |

neg. |

Jong 2003 |

|

Asarum crispulatum (=alternate species) |

herba(?) |

MEc |

China |

3376.9 |

neg. |

|

|

Asarum sieboldii |

herba(?) |

MEc |

China |

3.3 |

neg. |

|

|

Asarum fukienense (=adulterant) |

herba(?) |

MEc |

China |

16.6 |

neg. |

|

|

Asarum fukienense (=adulterant) |

herba(?) |

MEh |

China |

11.7 |

neg. |

|

|

Asarum sieboldii |

herba(?) |

ME |

China |

neg. |

neg. |

Schaneberg 2004 |

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

herba |

ME |

Jilin |

50.69 |

Jiang 2004 |

|

|

Asarum sieboldii |

herba |

ME |

Jilin |

71.06 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

herba |

ME |

Jilin |

351.1 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

herba |

ME |

Liaoning |

26.47 |

||

|

Asarum sieboldii |

herba |

ME |

Liaoning |

145.0 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum |

herba |

ME |

Liaoning |

neg. |

||

|

Asarum sieboldii var. seoulense (A) |

radix |

ME |

Hong Kong |

0.19 |

Zhao 2008 |

|

|

Asarum sieboldii var. seoulense (A) |

radix |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.04 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (B) |

herba |

ME |

Hong Kong |

11.91 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (B) |

herba |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.34 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (B) |

planta tota |

ME |

Hong Kong |

5.30 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (B) |

planta tota |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.25 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (B) |

radix |

ME |

Hong Kong |

2.16 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (B) |

radix |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.15 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (C) |

herba |

ME |

Hong Kong |

6.14 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (C) |

herba |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.31 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (C) |

planta tota |

ME |

Hong Kong |

2.21 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (C) |

radix |

ME |

Hong Kong |

0.93 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (C) |

radix |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.05 |

||

|

Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum (C) |

planta tota |

WE |

Hong Kong |

0.09 |

Table 1: Content of aristolochic acid-I (AA-I) and aristolochic acid-II (AA-II) in different species of Asarum, different parts of plant and different modes of extraction. Officinal species with the part radix are marked green, other parts yellow, and non-officinal species pink. Contents of watery extraction of the officinal species are in bold, they equate to a content which is expected by a decoction. ME = methanolic extraction, MEc = extracted with cold methanol, MEh = extracted with hot methanol, WE = water extraction